Capital Gains Taxes- Paying Uncle Sam Less

By Russ Warren, Managing Director and

Tom Zucker, President

M&A activity has returned after taking a breather during the recent economic downturn, and it’s a seller’s market. Private equity and strategic acquirers alike are deploying cash to acquire middle market businesses at attractive multiples of healthy earnings. Yet, “it’s not what you sell for, but how much you take home after tax, that counts”. So, in addition to a market-based valuation of your business, it is worthwhile to have your tax advisor calculate the expected tax bite when planning a liquidity transaction. The key tax rate is that on long-term capital gains (LTCG) – the difference between basis and proceeds.

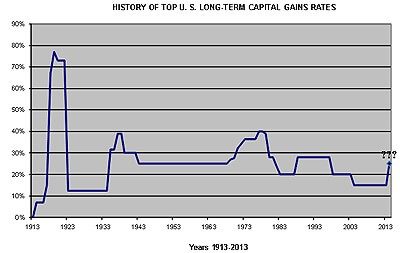

The LTCG tax rate has a volatile history since it began in 1913 as part of the income tax on individuals and corporations authorized by the 16th Amendment. It has been as low as 7% and as high 77%. At 15%, today’s maximum LTCG tax rate is the lowest it has been in the last 78 years

From 1913 until 1922, capital gains were taxed as ordinary income (at 77% when America was fighting World War I). In 1922, when the highest rate on income was 58%, a separate lower maximum rate for capital gains was adopted – 12.5%, until 1934, the second year of FDR’s first term. The rate was then raised to 32% for two years, 39% for two years and then 30% until the United States entered World War II in December 1941. Interestingly, from 1942 until 1968 – through WWII, Korea, Vietnam and with the Cold War on-going – the LTCG rate remained at 25%. It then crept up to 40% during Nixon, Ford and Carter years. Under Ronald Reagan it was cut to 20% for five years, then raised to 28%, which lasted for ten years, until, under Bill Clinton it was lowered to 20%. In 2003, under George W. Bush, the present rate of 15% was adopted with a sunset provision that now takes effect at the end of 2012.

The LTCG rate will go back up to 20% on January 1, 2013 if Congress takes no action. President Obama has stated he will not allow the Bush tax rates to be extended again. Will they be 20% again, or, with current budget deficits and a $14 trillion national debt, will revenue sources be on the table? If so, where better in Washington’s view to raise taxes, than to return capital gains to more historical levels? Pundits and tax-watching organizations diverge on their estimates, with Citizens for Tax Justice in January 2011 seeing a 25% LTCG maximum rate in 2013. Howard Gleckman, of the Tax Policy Center writing in the Christian Science Monitor in April 2010 said his “best guess is that the top tax rate on capital gains and dividends in 2013 will be almost 24%.” In February 2011, The Kiplinger Tax Letter said Obama wants Congres

While many factors enter into choosing the best time to sell a specific business, the prospect of paying more to Uncle Sam if the sale (of all or part) of that business closes after December 31, 2012 is already on the minds of some savvy owners contemplating an exit event within the next three years or so. Consider the following two hypothetical examples.

Today, if a business owner has $10 million in long-term capital gains, the tax at 15% will be $1.5 million. However, if the LTCG rate were to return to 28%, the extra $1.3 million tax bite would reduce take-home proceeds from $8.5 million to $7.2 million, a 15% shrinkage loss for family and philanthropic uses.

Alternatively, to realize today’s after-tax proceeds at higher future LTCG rates (and a constant pricing multiple), the business would have to generate a significantly higher Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortization (EBITDA) as shown below (in $000s).

| LTCG Rate | Required EBITDA | Assumed Multiple | Required Proceeds | Taxes | Take Home |

| 15% | 2,000 | 5 | 10,000 | 1,500 | 8,500 |

| Future Rates? | |||||

| 20% | 2,125 | 5 | 10,625 | 2,125 | 8,500 |

| 25% | 2,267 | 5 | 11,333 | 2,833 | 8,500 |

| 30% | 2,429 | 5 | 12,143 | 3,643 | 8,500 |

| 35% | 2,615 | 5 | 13,077 | 4,577 | 8,500 |

Where do you think the long-term capital gains rate is going, and how will that affect your plans? How much would you need to increase your revenues at a constant profit margin to cover the added tax burden, and how long would that take?

If you are an owner who intends to harvest your long-term investment soon, Uncle Sam is making an attractive limited-time offer – the endangered 15% Capital Gains Tax. But to take advantage of this offer, action is required. The typical sale of a middle market business – to an unrelated party, an ESOP or even management – requires six to twelve months (depending on factors often beyond the seller team’s control) from the time a financial advisor is engaged. To close a transaction by December 31, 2012, discussions and planning should begin soon. As that deadline draws nearer, buyers and advisors will get busier. In the world of taxes, 'almost getting it closed by the deadline' doesn’t count, and could cost you a lot of money.

If EdgePoint can be helpful to you, please call us at (216) 831-2430. Russ is at extension 207; Tom is at 204.

© Copyrighted by EdgePoint. Russ Warren can be reached at 216-342-5859 or via email at rwarren@edgepoint.com. Tom Zucker can be reached at 216-342-5858 or via email at tzucker@edgepoint.com.