Reflections on 40 Years in Middle Market Mergers & Acquisitions – Part 3 of 3

By Russ Warren,

Managing Director

Early on, a senior partner told me, “You know, I never thought much of experience until I got some.”

Part 1 reflected on how emergence of the leveraged buyout, mezzanine financing and the ESOP in the 1970s and 1980s, multiplied transition options for middle-market business owners.

Part 2 reflected on mega-trends influencing business owners, acquirers and transactions as well as memories of The Association for Corporate Growth.

Part 3 concludes with a personal perspective.

Think Grandly of Your Purpose – My life as a merger and acquisition advisor has been 40 years of learning, growing and experiencing afresh. There is no Groundhog Day. It is fulfilling to help a business owner with the most important activity of his or her career: the successful sale or acquisition of a business — that is, the harvest of years, perhaps generations, of creativity and hard work, or the building of a solid platform for future growth.

Taking Care of Business – My first decade in M&A was in a large organization, with staff and support services. That was good, because office technology then was primitive, connectivity as we know it was nonexistent, and daily business activities were far different than today. If you joined the workforce 10 or 15 years ago, it’s hard to imagine the pace of change in daily work routines over the last 40 years.

Since Leonardo da Vinci’s collaborator Luca Pacioli invented accounting in 1494, a pencil (or quill) and sheet of multi-column paper have been used to crunch numbers. I caught the tail end of that era.

Personal computing — using the term loosely — made its appearance in the 1970s. First, came Texas Instruments’ hand-held calculator (which computed present values and other financial necessities), then a Radio Shack TRS 80 (“Trash 80”). Ours housed a Buyer Database, and was the target of a hacker, trying the password “Duran Duran,” (which didn’t work). The laptop’s forerunner, a “luggable” Compaq brand computer, was a drag to haul through airports. Of course, a computer then was an island, not connected to anything else. And, nary a mouse nor an email were in sight. (For more color on computer wiki, read Walter Isaacson’s wonderful book,The Innovators.)

By the 1980s, you could build a spreadsheet using VisiCalc or SuperCalc PC software, and store results on a “floppy disc.” Often, you ran out of disc capacity before finishing, because early floppies held only 80 kilobytes. Later, an improved floppy could store 1.4 megabytes of information.

Before Google, research occurred in a library, and results took days, not an hour or two. Of course, the internet and search engines changed the world in many ways; some profound and obvious, some subtle.

Today, people expect you to do your homework, and they judge you on whether you cared enough to do it. The upside is, with thoughtful use of standard technology like Outlook, you can casually seem to have an awesome memory by asking about family members by name in a phone call with someone you haven’t talked to in years, even if you can’t remember where you parked your car.

Clearly, technology has also changed expectations of appropriate response time. We hear, “I sent you an email an hour ago — didn’t you get it?” Years ago, people had time to think and respond carefully. As psychologist Victor Frankl famously said, “Between stimulus and response, there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response.” There are times, like during M&A negotiations, when thinking before responding is a definite advantage.

The Bygone Business Lunch – Yes, Virginia, there really was a two-martini lunch, although it was more common with Madison Avenue’s advertising set than on Main Street. Many clients expected a drink at lunch, and expected you to have one, too. The only time I teetered on the edge of inebriation in business, was at the offices of a large London distiller of Scotch whisky. Asked what I wanted to drink, I named their most popular brand. The CFO said in a Highland brogue, “That’s a very good choice.” I’d take a sip, and he’d refill my glass. Fortunately, that was the last meeting of the day.

Life as an Entrepreneur – In 1987, I left the cocoon of a large firm and founded The Trans Action Group, a boutique middle market M&A advisory firm. Thus, I gained a special empathy for anyone who starts a business and meets a payroll. As a friend told me at the outset, “The highs are higher and the lows are lower.”

I learned to treasure loyal friendships. For example, the M&A team at Ernst & Whinney advised Bob Elman, a good friend, on his management buyout of DESA International, and when I left, he was seeking acquisitions. Bob said, “We’ll be your first client,” even before I had formed my legal entity.

Allen Ford, retired Senior Vice President of Standard Oil (Ohio), and Allen Holmes, retired Managing Partner of Jones Day law firm, were friends from our service together on the Case Western Reserve University Board. Allen Ford said he and Holmes were going to rent offices and share a secretary, and asked, “Would you like to join us?” Forget what I just said about the time between stimulus and response. I instantly said “Yes.” Now I had a client and some credibility. Life was great!

DESA was the only name on my first year cash-flow projection to become a client, but other clients came and we cash-flowed positive. Allen Ford did volunteer work on our first transaction, the sale of an ophthalmic equipment business owned by the father of another good friend, Fred Clarke. Allen Holmes gave pro bono legal advice, among other things dictating an indemnity clause so effective it drew admiration from many clients. I was indeed fortunate to have the support of such friends.

The uncertainty of a new enterprise was probably hardest on my wife. She was concerned, committed and supportive, asking daily: “Did you call John Smith back? How was your meeting this afternoon?”

I was on my own with computers — almost. Another good friend, Clint Alston, who ran the Ernst IT consulting practice, sent a young colleague over to help me set up shop, and tutor me in things digital. That’s when I discovered a basic rule of technology: Always go to the youngest person around, when you need help. Recently, the Dean of Case School of Engineering explained why this is so. “You and I are immigrants in the electronic age. Today’s students are natives.”

Each person in a small business shapes the culture. A former colleague, Frank Novak, joined the firm as an owner a year after founding. Over 21 years, we grew The Trans Action Group to seven professionals and closed 75 M&A transactions, 19 of them cross-border. From our offices in The Hanna Building, we also watched the early redevelopment of Playhouse Square and downtown Cleveland.

Time Marches On – In 2007, two key members left the firm (one to buy a business and the other to retire), and I realized I really enjoy recruiting clients and working on engagements, more than the compliance and administrative activities consuming so much of my time. After considering the best path, we chose EdgePoint, a fast-growing boutique M&A advisory firm with the same values and mission: to bring top-quality professional M&A services to owners of middle-market businesses.

I was happy to trade my former CEO duties for those of Managing Director, developing new business and serving clients. I studied for the first time since the CPA exam decades before, and got my securities licenses. Years ago, I waited a month for the CPA exam results by mail. This time, it was a very long minute, staring into a computer screen. Both results were well worth waiting for.

As an M&A professional, it is reassuring that my own M&A transaction was successful, and I continue to enjoy working in an energized small-firm environment.

The “F” Word: Fees – It’s curious. Owners who willingly pay up for a fine piece of equipment may be irrationally fixated on professional fees in an M&A transaction. Fees are earned only when the seller’s transaction closes. For a seller, creating orchestrated competition among motivated buyers generates value far greater than the advisor’s fees. To reinforce the value proposition, we use win-win performance-based fee structures, like an incentive percentage above a pre-agreed value. Value-adding service at each stage and frequent communications create a satisfying client experience.

To illustrate, an owner came to me because his general manager wanted to buy the business. He was willing to sell, but said the offer seemed low. It was. We obtained offers well above what the employee could afford. The outcome was a strategic transaction at twice the original offer, with a key role and phantom stock for the employee. Our transaction fees were not an issue.

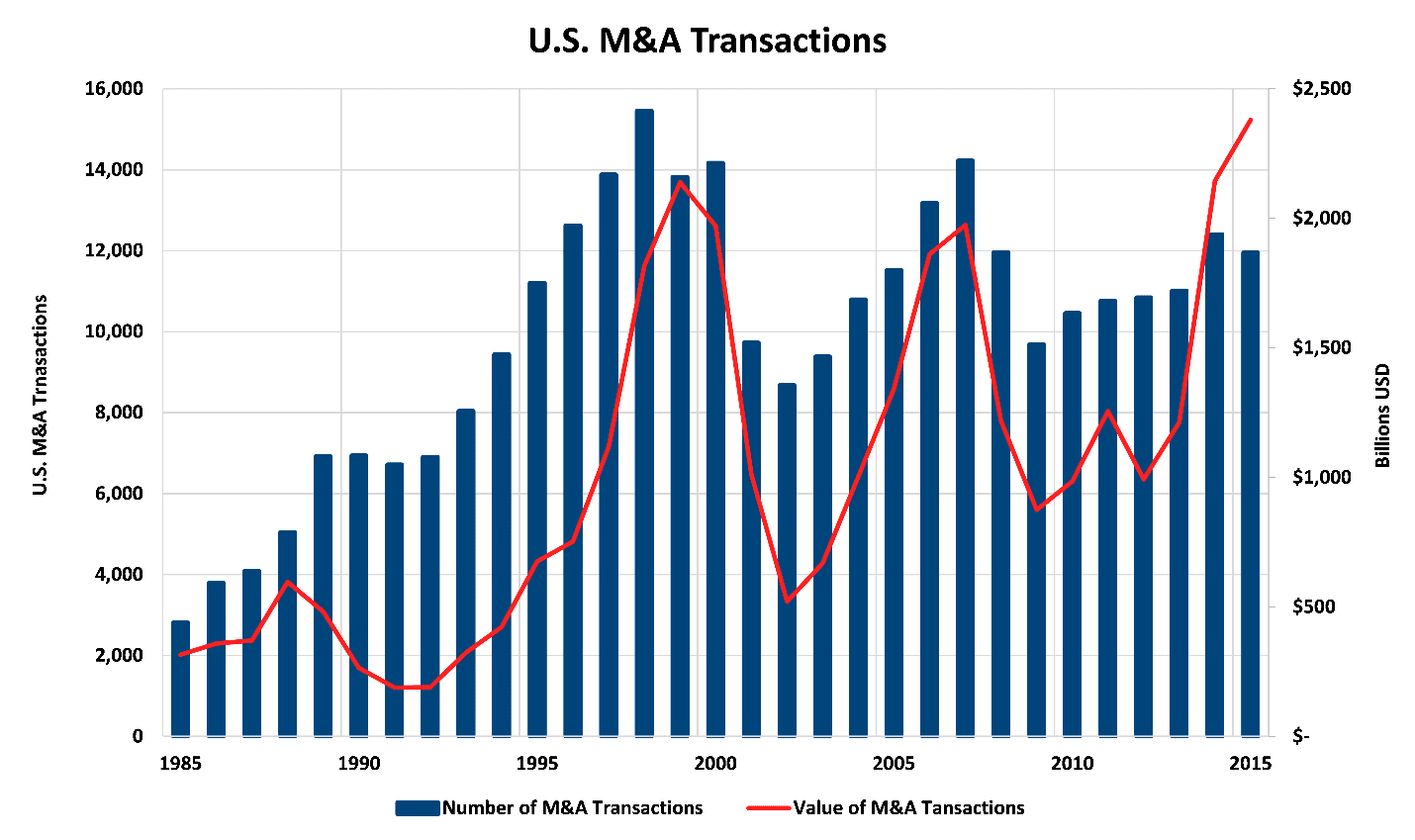

Roller Coaster Ride – As you know, M&A activity rises and falls with economic conditions and financing markets. Over 40 years, it has been quite a ride for owners, acquirers and advisors. The graph below conveys transaction variability since 1985. (Apparently, anything older is prehistoric to the Institute of Mergers, Acquisitions and Alliances, source of this data.)

The smaller-transaction market (think blue bars above) is more stable than mega-deals (dominating the red line) because large transactions are more closely tied to the stock market, and private businesses have strategic and shareholder needs to address, regardless of market conditions. However, many sellers wait too long to pull the trigger. For the owner that misses the “fleeting moment of perfect flavor,” it usually takes at least five years (another growing season) for the fruit to ripen again.

Indelible Clients – While this article is about to degenerate into stories, you also get a “moral” or lesson with each.

Engaged by the Asian Development Bank to improve venture-capital access in five developing economies, we learned there were “Business Development Companies,” which sounded like venture capital firms. Why were they not working? We learned BDCs required collateral, which applicants did not have—so the BDCs made no investments. As it turned out, BDCs were run by former bankers, who continued their old habits. Moral: People can be more important than a business model.

Bob Elman of DESA demonstrated his character a second time. We found a strategic acquisition, and negotiated a Letter of Intentto buy a generator manufacturer. The owner died suddenly before closing. He had told his wife he liked the buyer, so after a respectful time, the deal was on again. Bob said, “I know the business isn’t worth as much without him, but I can’t renegotiate under these circumstances.” We closed on the original terms. That year the hurricane season was intense and DESA sold every generator it had in stock or could manufacture. Moral: Sometimes, doing what feels right can pay.

A client’s president told me during the sale process: “I’m probably the only person in the company that thinks no one else knows what’s going on.” Moral: Confidentiality is very important, but employees seek job security. Working for a company with no visible succession plan is not security.

We sold a Tier 2 automotive-plastic-components manufacturer to a NYSE buyer. The heart of the seller’s operation was a machine with many in-house engineering changes that gave it a competitive edge. The buyer intended to relocate everything to one of its facilities. The seller said, “I really advise you not to move that machine. It has a lot of ‘black art.’” With a seemingly adequate stockpile of parts, the buyer disassembled the machine and shipped it off. They could not make it work right in its new location, and their largest customer ran out of critical parts. Two Morals here: First, buyers should take a seller’s warning seriously. Second, protect your client: the asset purchase agreement had three ways seller could meet earn-out provisions, any one of which required payment—and seller collected, in spite of buyer’s self-inflicted disaster.

What Does M&A’s Future Look Like? – In this three-part article, I’ve tried to convey my take on the Middle Market’s evolution with “thoughtful irreverence.” I hope it’s been illuminating. With no special insight on tomorrow, I eagerly look forward to dealing with interesting new developments certain to arise in our fast-paced business world. I’ll likely need to update this article in a few years—so stay tuned.

© Copyrighted by EdgePoint. Russ Warren can be reached at 216-342-5859 or via email at rwarren@edgepoint.com.